![]()

Staging conventions

I wrote a colleague, asking him if he had seen a 1980 production of Hamlet which seems inspired by the notion that the words of the ghost are the product of Hamlet's over-heated brain. Here's his reply.

|

(E-mail, though it have no tongue, will speak with most miraculous organ - I have just found your wafting.) Whiles memory holds a seat in this distracted globe, I think that the production you mean is one that I saw at the Royal Court with Jonathan Pryce as Hamlet. It was directed by Richard Eyre and opened on the 2 April 1980. The best thing about it was the tiny claustrophobia-inducing set and Jill Bennett as Gertrude. Pryce did indeed utter the ghost's lines himself. He did them in a sort of Noh theatre grunt which came off like a Shakespearean waste disposal unit. The idea, it seemed to me, was that Hamlet was possessed by a ghost rather like in the Omen films - in fact the parallel was too close and I think that was why it raised titters. I wish I could remember what they did about the others who SEE the ghost. I do remember feeling that the idea did not work well even though I like what it suggests about the evil intention of the ghost. Done this way however, it took away any appeal or temptation in the ghost - who became a frightening and diaphragm-rending voice of command over which H had no control. To me, it had the effect of making H appear to be a real nutter rather than someone who becomes gradually ensnared by a cause that appears to have some appeal. If I wanted to lime Hamlet's soul, I would choose a better way than disguising myself as a severe attack of gastroenteritis. --Paul Whitworth |

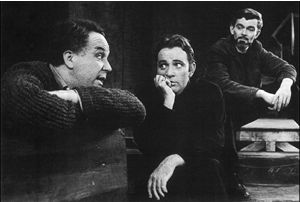

A similar staging was used in the 1964 production staring Richard

Burton and directed by Sir John Gielgud. Here is Eleanor Porsser's comment

on the staging.

|

|

The 1964 Gielgud-Burton production in New York was typical. The Ghost did not appear. It was a mere shadow on the backdrop, a disembodied voice filtered through an echo chamber. All the lines were exquisitely sung in the quavering tones of a dying saint. All of them, that is, except those that were too flagrantly sickening or obscene. These -- the descriptions of the poisoning and the picture of lust preying on garbage -- were cut. In modern productions, are we ever really terrified or shocked by what the Ghost says and the way he says it? The actor is usually cast for his resonant voice and he knows it. Traditionally he chants the lines in mellifluous tones of melancholy tenderness -- all the lines, including those of agony, pride, disgust, hatred and urgency. -- Eleanor Prosser, Hamlet and Revenge, Stanford Univ. Press, Stanford,1971, p.142. |

Ironically, the very thing that Prosser finds most objectionable, is the one that Gielgud considers to be his principal stroke of genius.

| I felt that my only contribution to this production that had any merit was in my treatment of the Ghost. I had a great black shadow which suddenly took shape above the stage and hovered over Hamlet throughout the scene, then slowly moved away until it disappeared. --John Gielgud, Shakespeare-Hit or Miss?,Sidgwick and Jackson, London, 1991, p.41. |

Gielgud's ghost spoke with his own soft and melodious voice. More often than not, the ghost has a resonant base voice in modern productions, but his physical presence is reduced by staging which involves darkness, mist, shadow, or vague special lighting.

An exception to this rule is seen in Richard Salzeberg's ghost in the 1986 Shakespeare Santa Cruz production. In this case, we are seeing a very real ghost.

In the early twentieth century, film makers began using double exposures to give the impression of a transparent or translucent ghost. Here are examples from E.Hay Plumb's 1913 silent film starring Sir Johnston Forbes-Robertson and John Barrymore's 1933 screen test.

|

|

More typical is the blue light special used to tint the ghost in Rodney Bennett's BBC production.

Effectively, either the ghost does not appear at all, or he comes bathed in a special light or veiled in mist. He is hard to see, but easy to hear.

| The play begins. A player comes on under the shadow, made up in the

castoff mail of a court buck, a wellset man with a bass voice. It is the

ghost, the king, a king and no king, and the player is Shakespeare who

has studied Hamlet all the years of his life which were not vanity

in order to play the part of the spectre. He speaks the words to Burbage,

the young player who stands before him beyond the rack of cerecloth, calling

him by name: Hamlet, I am thy father's spirit. bidding him to list. -- James Joyce, Ulysses, p.185 |