![]()

Ophelia's Madness

That Ophelia appears without a past and with no friends to tie her to a larger world, and that she is defined largely in relationship to Hamlet and Polonius; both seem consistent with R.D. Laing's diagnosis of her as schizophrenic. For Laing, the essence of schizophrenia lies in the absence of the essential person.

| Praecox - From the term dementia praecox formerly used to denote what we now generally call a form of schizophrenia occurring in young people which was thought to go on to a conclusion of chronic psychosis. This 'praecox feeling' should, I believe, be the audience's response to Ophelia when she has become psychotic. Clinically she is latterly undoubtedly a schizophrenic. In her madness, there is no one there. She is not a person. There is no integral selfhood expressed through her actions or utterances. Incomprehensible statements are said by nothing. She has already died. There is now only a vacuum where there was once a person. - R.D. Laing , The Divided Self , Penguin Books, London, 1959. p. 195n. |

Frequently, Ophelia appears to be caught up in infantile regression. The fully formed adult disappears, and only a childlike ghost of the former person remains in her place. Such an interpretation of the character informs Laurence Olivier's 1948 production of Hamlet. Given Olivier's avowed belief in Freudian psychology, his depiction of Opheila's childhood regression is a directoral choice frought with irony. By making her into a prepubescent child, Olivier skirts all the suggestions of repressed sexuality wirtten into her part.

On the other side of the argument, Elaine Showalter sees a pattern of diagnosis in early psychology which focuses on the expression of sexual repression. While Elizabethan men were frequently thought to be aflicted with melancholia, women rarely were. Their particular form of madness was more related to hysteria -- an affliction which was considered to be particularly feminine.

| hysteria-[NL, fr. E hysteric (Fr. hystericus of the womb, Fr. Gk hysterikos, Fr. hystera womb + ikos -ic; Fr. its being originally applied to women thought to be suffering from disturbances of the womb) + NL -ia] |

| Clinically speaking, Ophelia's behavior and appearance are characteristic of the malady the Elizabethans would have diagnosed as female love-melancholy, or erotomania. From about 1580, melancholy had become a fashionable disease among young men, especially in London, and Hamlet himself is a prototype of the melancholy hero. Yet the epidemic of melancholy associated with intellectual and imaginative genius 'curiously bypassed women.' Women's melancholy was seen instead as biological and emotional in origins. - Elaine Showalter,"Representing Ophelia: Women, Madness, and the Responsibilities of Feminist Criticsim" in Susanne L.Wofford (ed.), Hamlet, Bedford Books, Boston, 1994. p. 225. |

We also frequently see Ophelia played as a women who has overcome, through madness, the sexual repression we see played out in the first three acts of Hamlet. Here are examples from the 1980 BBC television production and from Franco Zeffirelli's 1990 film version.

|

|

|

In her fascinating essay, Elaine Showalter argues that Ophelia's madness is specifically "the product of the female body," and that Elizabethan conventions of depicting female insanity were observed in the play. She then goes on to chart the progress of those depictions in portraits and interpretations of Ophelia that have succeeded the original creation of Hamlet. Interestingly enough, subsequent to the virtual explosion of interest in psychology in the first decades of the 19th Century, there were numerous fascinating and influential representations of Ophelia in western art.

|

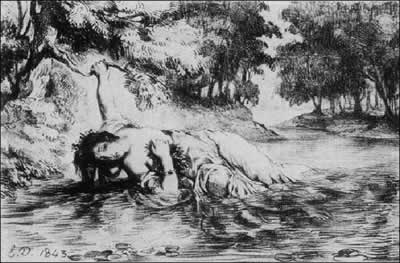

Eugène Delacroix - La Mort d'Ophélie (1843)

| The most innovative and influential of Delacroix's lithographs is

La Mort d'Orphélie of 1843, the first of three studies.

Its sensual languor, with Ophelia half suspended in the stream as

her dress slips from her body, anticipated the fascination with the

erotic trance of the hysteric as it would be studied by Jean-Martin

Charcot and his students, including Janet and Freud. Delacroix's interest

in the drowning Ophelia is also reproduced to the point of obsession

in later nineteenth-century painting. The English Pre-Raphaelites

painted her again and again, choosing the drowining, which is only

described in the play. - Elaine Showalter,"Representing

Ophelia: Women, Madness, and the Responsibilities of Feminist Criticsim"

in Susanne L.Wofford (ed.), Hamlet, Bedford Books, Boston,

1994. p. 229. Ophelia, with her exposed breast and swooning abandon, about to be swept away by the current, invests the moment with an explicit erotocism, in addition to the voyeurism implicit in any viewing of her private bath/death. - Gary Taylor, Reinventing Shakespeare,Oxford, 1989. p.214f. |