![]()

Repressing the Roots

|

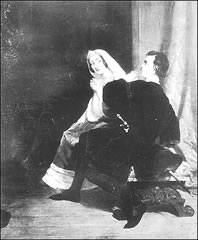

In Richard Dadd's 1840 oil paintingof the closet scene,

it appears that the ghost was once painted into

the upper left side of the scene and then removed.

The result is that Hamlet does end up staring

into empty space, just as Gertrude describes it.

On the surface, Oedipus Rex and Hamlet seem

to be far apart in regard to the protagonist's competition with his own

father for his mother's affections. If anything, Hamlet expresses unbending

affection and loyalty towards his father, and seems to be motivated throughout

the play by the desire to do right by him - even after his death. Freud

explains the difference between what he takes to be an innate universal

psychological mechanism and the accepted range of expression of civilization

with the notion of repression. That Hamlet has fundamental urges which

are not visible in the course of the play is a tribute to the energy he

has invested in repressing them. Freud allies advances in civilization

itself with the increase of repression.

| Another of the great creations of tragic poetry, Shakespeare's Hamlet, has its roots in the same soil as Oedipus Rex . But the changed treatment of the same material reveals the whole difference in the mental life of these two widely separated epochs of civilization: the secular advance of repression in the emotional life of mankind. In the Oedipus the child's wishful fantasy that underlies it is brought into the open and realized as it would be in a dream. In Hamlet it remains repressed; and - just as in the case of neurosis -- we only learn of its existence from it's inhibiting consequences. - Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, tr. James Strachey, Avon, N.Y. 1965. p.298. |

Hamlet has evidently repressed entirely any urge to kill his own father.

For the Freudian critic, this means not only that he has put more of himself

into inhibition, but also that he runs greater risk of mental illness. What

we have is a situation where the greater the Oedipal urge, the greater the

need to repress it, and the greater the repression, the greater the risk

of illness, and the more severe any such illness is likely to be.

| We note -- if the Elizabethan language is translated into modern English -- the symptoms of dejection, refusal of food, insomnia, crazy behavior, fits of delirium, and finally raving madness; Hamlet's poignant parting words to Polonius ("except my life", etc.) cannnot mean other than a craving for death. These are undoubtedly suggestive of certain forms of melancholia, and the likeness to manic-depressive insanity, of which melancholia is now known to be a part, is completed by the occurrence of attacks of great excitement that would nowadays be called "hypomanic", of which Dover Wilson counts no fewer than eight. - Ernest Jones, Hamlet and Oedipus, W.W.Norton, NY 1976. p.22. |